05 Apr When Knowledge Isn’t Enough

In the last post I spoke a bit about the power of knowledge in student comprehension, and I shared a few thoughts on how to leverage it in class. That knowledge is an important basis for reading comprehension is, by now, well-trod ground (see here, and here, and here and, well, you get the point).

I’m a total believer. Building background knowledge allows students to tackle more challenging, complex texts – and those texts end up building student knowledge far faster than simple texts could.

But what of those moments when our background knowledge exists a bit fuzzy or incomplete? That feels pretty typical – especially if our students are curious to read about new ideas. On what else can readers rely?

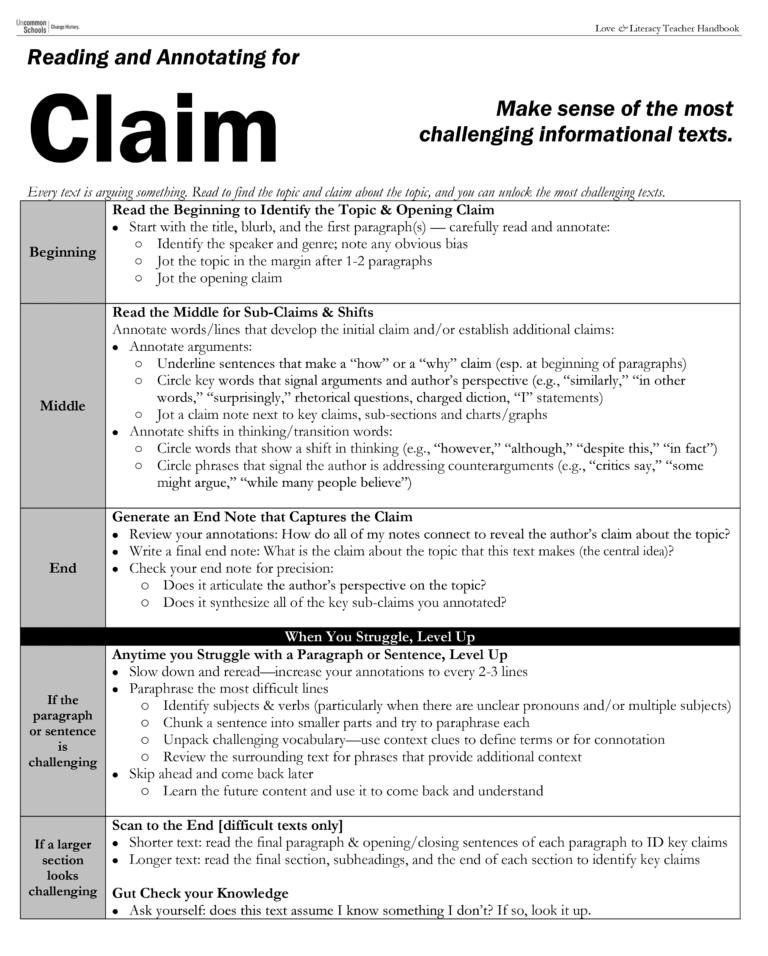

To help answer, my colleagues and I developed a framework to guide students in grades 5-12. It starts with a premise: text is claim. All texts (from essays to encyclopedias to Instagram posts) make an argument about the world (even if the argument is as simple as “these are the causes of the Civil war” or “this is what the president said on Tuesday” or “this cereal is fortified with 10 essential vitamins and minerals”).

If we look at informational texts as collections of claims, we have a pathway to comprehension: we can read to identify them. [1]

What’s more, it’s then in our power to decide if we accept those claims. There are a few advantages to reframing text this way for students:

- It helps students know what to “look for” when they read informational text, since in their initial reading they are usually looking for its major claims.

- It helps students maintain a critical distance from what they read, pulling authors off their pedestals and getting them closer to eye level. An informational text – no matter how reasonable sounding – is just an author’s argument. That makes it subject to critique and verification.

- It normalizes struggle, preventing students (and those of us teaching them) from shying away from difficult encounters. Moments of struggle become natural opportunities to use new tools, and this is an important component of student literacy development.

From there, the framework becomes common language we use with students when they tackle informational texts – a habit of mind that shifts the way students interface with what they read. Here’s what we share. [Click on the image for the PDF!]

Researchers sometimes talk about a text’s coherence. In lay terms (sorry, researchers!), this refers to the signals that texts send to help readers understand what’s happening. For example, a word like “however” cues me that a text is about to shift in meaning. When I see the phrase “in other words” in a tough paper, my pen is already on the page, ready to annotate.

Studies show that high coherence texts can help compensate for missing background knowledge… which is all the more reason to teach students to be sensitive to these when they read.

We also tried to normalize the feeling of being stuck – with a section on how to “level up” when this happens. It’s important for teachers not to be afraid of student struggle – but it’s even more important for students to feel that way. Getting stuck, realizing it, and changing strategy should feel as normal as changing gears on a bicycle.

The bottom line? All of us are readers in struggle, at least at some points in our lives. (Just ask me to read an engineering textbook and I’m right there.) If your curriculum is challenging, your students will find themselves in moments of struggle, too. A strategy for processing informational texts can:

- Help students identify a text’s claims and critique them, affording clarity and critical distance.

- Build habits of mind that attend to text coherence features, which can help students when there are gaps in background knowledge that they cannot fill in the moment

- Normalize struggle with difficult texts, and give students tools to use when they do

In addition to building background knowledge (which, again, is vital), teaching students habits of mind to use when they encounter difficult texts is a great way to help them tackle the most challenging texts and build some healthy perspectives about their role as readers.

Struggle isn’t something for students to fear. Where we grapple, we grow.

—

[1] This builds on Johnson and Afflerbach’s topic-comment model, one of coolest things to come from the 1980’s after jean jackets and The Empire Strikes Back. We were very much inspired by the work that Jeff Wilhelm and Michael Smith do to build on that research in Diving Deep into Nonfiction, where they suggest lessons to help students attend to the conventions of informational texts, including the topic-comment approach. Worth your time, IMO!