14 May Four Things Dutch Still Life Teaches Us About English Curriculum

Earlier this week, the New York Times posted a terrific piece about Dutch still life painting. It was a wonderful coincidence, since I’ve been thinking a bit this year about the genre.

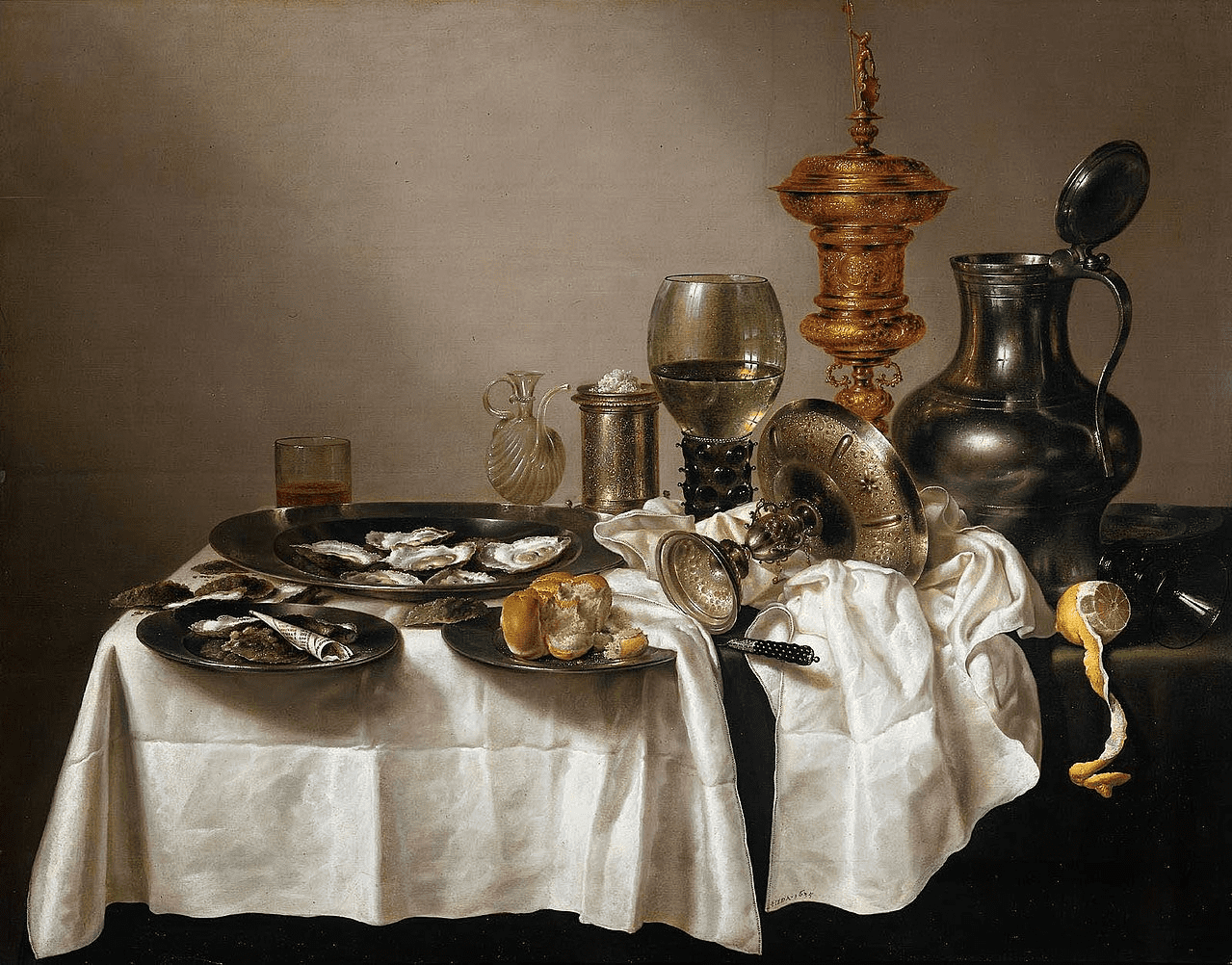

I’ve been imagining this type of painting – which emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries – as an analogy for curriculum because it reminds me why humanities study can be so fulfilling. Younger me looks at the above painting and says “OK, these people really liked paintings of messy tables where nothing is happening. Boooring.” More experienced me, I hope, can see a bit more.

I think our study of literature works the same way. At its heart, an English curriculum might ask: how do we get students from “It was an OK story, I guess” to deep, probing appreciation or analysis? From a curriculum design standpoint, I think there are at least four answers still life painting has for us.

Broad Knowledge BuildingThe first thing this type painting reminds me of is the need for curricular knowledge building.

For example, if you don’t know that Dutch painters were being funded by a flourishing mercantile class (rather than the church or royalty), the choice of an overstuffed table might be confusing or even off-putting. If you know, it’s meaningful. This isn’t just “we had a party and there was lots of food.” It’s a representation of Dutch wealth and identity and success.

Or take the peeled lemon. Believe it or not, these appear in about half of Dutch still lifes. Why? Lemon peels were hard to paint – including them was a way for Dutch painters to flex on each other. Turns out, lemons were also hard to come by in 17th century Holland, so they’re also another nod to the commerce and wealth of the territory.

As cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham frequently argues, knowledge building is central to critical thinking. Without knowledge, we’re left with little to think about. From my seat as a literacy director, it’s not that reading skills don’t matter, just that they aren’t really meaningful in isolation. Kids don’t need 200 lessons on how to make an inference.

Instead, when we design curriculum, we can plan how we’ll weave knowledge into our lessons and unit plans – so students can put those skills to use in the service of understanding complex texts that challenge them and build their knowledge even further.

Technical Knowledge Building

The examples I just gave are probably close to what a lot of people think about when we discuss student knowledge – specific facts about the world that help us make sense of what we read. Let’s call it “broad knowledge” for now.

But there’s another category of knowledge building that gets discussed less often, something I’ll call “technical knowledge.” Consider that lemon again. Because I’ve read a bit about still life painting, I know that lemons might be a symbol for the traps of excessive pursuit of wealth – they are rare and beautiful – but also bitter. In fact, most of the things displayed have some sort of symbolism in still life paintings, often religious. If you know these, they jump out. If not, they’re probably just food.

This is where skills do come into play a bit, since our curriculum helps students identify when something might be a symbol, how to go about determining it, and how to make a case based on the evidence they’ve gathered. But even in this case, much of a skill still relies on technical knowledge.

Consider the tipped over goblet, which the NYT notes “could be a ski lift, for how directly it carries us from the bread roll … to the gold and pewter vessels.” From my days teaching photojournalism, I know that a diagonal line leads the eye in an image. The critic here isn’t making an observation that no one else could; they’re deploying knowledge of composition to make sense of the painting. Again, either someone has taught you that, or you’re just left to figure it out on your own.

Our ability to see nuance and subtlety, I’m convinced, comes often from knowing where and how to look.

Perspective-Taking

But viewing a still life isn’t solely about the broad and technical knowledge of the viewer. It also relies on the perspective we view from. If we know what being a woman was like when Shakespeare wrote, can we see, say, Lady Macbeth as something other than a villain?

One of the pillars of Gholdy Muhammad’s historically responsive teaching framework is the ability to read “print texts and contexts with an understanding of how power, anti-oppression, and equity operates throughout society.” When we engage this way, we ask ourselves who is portrayed and how – and who isn’t and why. You could argue it’s really just the application of a third type of knowledge – one of history – combined with the desire to consider multiple perspectives.

Our ability to engage Dutch still life with this lens reminds us to consider the global nature of the items depicted. On one hand, they are a symbol of Dutch maritime dominance. It’s likely that’s how Dutch patrons saw them. But, from another vantage, they are a reminder of the colonization and enslavement that led to Dutch wealth. Notes the Times:

The plantations of Dutch Brazil, worked by enslaved Africans, produced hardwoods and sugar — and also lemons, their blossoms harnessed for perfume, their peels candied and shipped back to Amsterdam.

This isn’t trying to find the grey cloud behind a silver lining (or goblet, as it were). These ideas begin implicitly by the inclusion of things like the lemons and sugar, but ultimately would grow to be more explicitly stated, as enslaved peoples would eventually be depicted among the commodities of still life paintings. That may be hard to countenance, but it’s a crucial part of the picture.

Connection

What are we to make of all of this? It’s interesting, certainly, but interesting alone doesn’t necessarily cut it in class. Ultimately, what drives our curricula is the ability for it to show how the humanities can pose questions that matter, ones that are relevant today and that invite students in to consider how to engage with the world.

You might think of each unit and lesson you teach as a story/journey – a quest to grapple with some big ideas or challenging truths. That’s why so many of us organize our English units not just around specific texts, but around the essential questions they pose. Is freedom more important than security? Why do bad things happen to good people? English class is our change to hash it out with authors and each other.

In terms of Dutch still life painting, here’s one example, posted by Julia Fiore in her discussion of the dark side of the genre:

What are the true social costs of today’s most sought-after items, and why do people love to show them off? Nikes, iPhones, and designer clothes are imported from many of the same international sites the Dutch traded with hundreds of years ago (and employ similarly dubious labor practices).

Can you see your own class coming alive to talk about this? To what extent do we define ourselves based on status and possession? If we know it’s “bad,” why do we do it anyway? And what are the costs when we build our identities around luxuries wrung from the sweat of others’ brows? When we plan English units, we can emphasize the same types of inquiry.

There’s so much tucked in the folds of this quiet table scene. Our curricula can give students the same keys viewing still life demands: broad knowledge, technical knowledge, the ability to take multiple perspectives, and a way to connect personally and meaningfully to what we teach. If we do, we help our kids harness the power of the humanities in a way that lets the see more than the table and the lemons… but all the way to the violent, rich, crushing, beautiful world that lies beyond.