06 Apr Get Meta on Genre to Bolster Reading Skill

these girls

deserve

to have

better stories

than the ones

where they are murdered

because they love

with too much

of their

hearts

– Amanda Lovelace, The Princess Saves Herself in This One

In his seminal Before Reading, scholar Peter Rabinowitz tells the story of a Mark Twain joke gone awry. Buried in A Double-Barreled Detective Story is the following piece of super-purple prose. Keep an eye out for the sleeping esophagus [yes, you 100% read that correctly]:

“It was a crisp and spicy morning in early October. The lilacs and laburnums, lit with the glory-fires of autumn, hung burning and flashing in the upper air, a fairy bridge provided by kind nature for the wingless wild things that have their home in the tree-tops and would visit together; the larch and the pomegranate flung their purple and yellow flames in brilliant broad splashes along the slanting sweep of woodland, the sensuous fragrance of innumerable deciduous flowers rose upon the swooning atmosphere, far in the empty sky a solitary oesophagus slept upon motionless wing; everywhere brooded stillness, serenity, and the peace of God.”

Thing is, Rabinowitz reports, Twain was surprised that people read right past this passage – so much so that he had to include a footnote so that they’d get the joke. As my college journalism professor used to say, if you have to announce to people you’re writing satire, something has gone horribly wrong.

Rabinowitz notes that Twain was playing with some of our expectations of genre – mainly that setting descriptions don’t much matter in detective stories of the 1800’s. Readers, by instinct perhaps, knew this was a place to skim – so the fact that they raced past his description makes sense.

This sort of genre instinct is hard won. It comes through years of independent reading and exposure to different types of texts and the logic behind them. But that doesn’t mean teachers cannot help build it with students in the meantime.

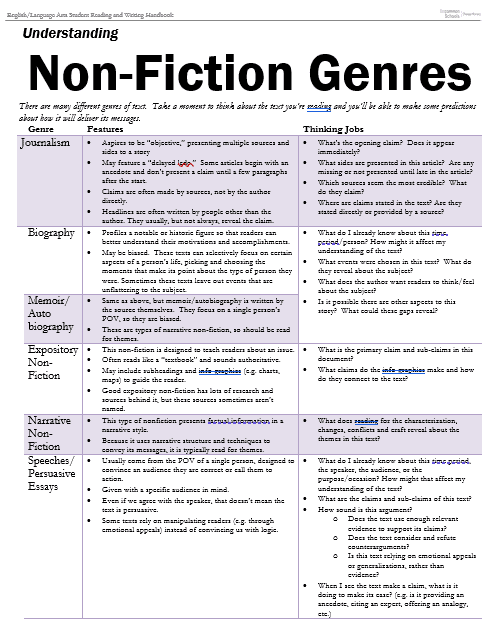

My colleagues and I spend a good percentage of our time analyzing student work. Turns out that knowledge of genre is a frequent sticking point, especially in the middle grades. For example, kids get tripped up on an article because they don’t know that often the first paragraph is not always the most important, or they miss the point of a fable because they don’t scrutinize its resolution for a moral. In our middle schools, we try to make a point of talking about genre when we launch new texts, and we provide the following guidance to help students think about different genres.

Genre instinct is a type of reader’s savvy we can gift to kids. When I was a 10th grader, I remember actively talking with friends about which parts of the long Victorian novels we read were most likely to contain

important moments for discussion. [We theorized it was the beginnings/endings of chapters.] It didn’t mean we didn’t read the whole book, but we were developing instincts around when to pay extra attention. (For a modern example, consider that my wife is perfectly capable of scrolling Instagram while we watch Star Trek Picard, but she is always able to lower her phone when a key development is about to occur.)

And if we can become discerning about genre in the middle grades, perhaps a next step in high school is to start talking with students about tropes – which I know many teachers do. Experienced readers are thoughtful about how common conventions appear and are altered by authors.

Consider, for example, Constance Grady’s breakdown of Tamsyn Muir’s wonderful Gideon the Ninth. Grady shows exactly what’s powerful about understanding tropes in her analysis: she names the patterns that genres typically follow, and she can point out when Muir is playing with them for effect. We talk about knowledge building as key for student comprehension, but I’m convinced there is fertile ground in the less-discussed meta-knowledge about how genres often work.

Recognizing the tropes and expectations we tend to take for granted allows us to better appreciate when authors bend these (as in our epigraph), or try making these moves ourselves when we write.

The bottom line?

In younger grades, being explicit about genre conventions is a powerful way to help students build some readers’ instincts. The guidance above will hopefully help you “preview” genres with students when they encounter new texts.

As readers develop, consider discussing tropes, too – that helps students develop a critical lens for the texts they read. When our 8th graders read graphic novels, for example, we pause to explore the “women in refrigerators” trope. (We also use texts like the one in the epigraph to challenge common expectations.)

One of the best ways for our students to develop genre instincts is a balanced, extensive reading diet. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be explicit about conventions ourselves – welcoming developing readers

into the kitchen to see how many of these recipes work… and how they can be changed.