17 Oct How to enhance Literary Analysis Part 2 – Tuning Reading Radar

“It’s as if the key to the treasure is the treasure.” – John Barth, Chimera

In my last post, I talked about some moves you might use to make the steps of analysis more transparent for students, arguing that this – along with knowledge building – were a huge support for analytical growth.

But I left out something pretty huge: just how are students supposed to know what to analyze? To answer, let’s consider the opening of Ann Petry’s The Street:

There was a cold November wind blowing through 116th Street. It rattled the tops of dustbins, sucked window blinds out through the top of opened windows and set them flapping back against the windows; and it drove most of the people off the street in the block between Seventh and Eight Avenues except for a few hurried pedestrians who bend double in an effort to offer the least possible exposed surface to its violent assault…. It did everything it could to discourage the people walking along the street. It found all the dirt and dust and grime on the sidewalk and lifted it up so that the dirt got into their noses…

The opening continues like this; you can read more here. Now, we can look at this paragraph and quickly say – hmm, something’s happening with the wind here. Maybe the setting is a metaphor? If we have that thought, it’ll guide us as we read – a theory we can test. But just how did we come up with that?

I sometimes call this “reading radar” – the ability to spot the a-ha moments in a text. But in my earlier years of teaching, I found it stressful to coach students on this. After all, I reasoned, wasn’t this skill just the product of years of experience reading?

In part, the answer to my question was: yes. In Before Reading, Peter Rabinowitz makes a thoughtful case for wide student reading and the power of readers to spot calls to attention in a text, especially when they are familiar with the genre. For example, I know that opening passages in fiction tend to be important, and I also know that settings can often be symbolic, especially in literary fiction. (Think of the two-page

description of Janie’s tree in Their Eyes Were Watching God.) These rules of notice help guide me as I read, and they are the product of experience.

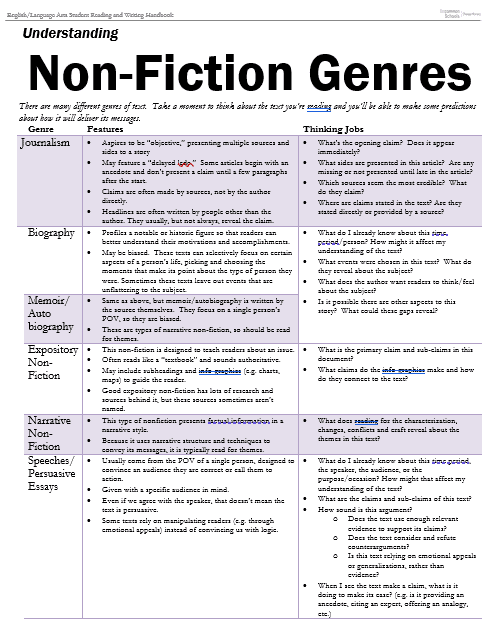

But that doesn’t mean teachers can’t speed up their acquisition. (What is school if not guided experience?) If we expose students to lots of genres and help make some of these rules explicit, we can prepare students to spot them themselves. For example, at Uncommon, we provide our middle schoolers with guidance on the thinking jobs required by various genres, helping them consider what expectations they have from the text and what they might attend to while reading it. A great time to visit this is any time you’re encountering a new text (whether the genre is familiar or not). Click on the image at right if you’d like to download our current draft — a work in progress!

But there’s another technique students can use to spot some of these calls when reading, and it comes down to sensitivity at the sentence and paragraph level. I knew, in part, to analyze the wind because the language being used with it was so charged. The words just hummed. What internal rules helped me spot that?

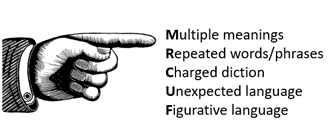

To unpack that thinking, we’ve used an acronym called MR. CUF. (Forgive this, I can’t think of a better one, but reader suggestions are encouraged!) Cues to dig deep include: multiple meanings, repeated words/phrases, charged diction, unexpected language, figurative language.

Let’s give it a test drive. In the last blog post, I looked at “In a Station of the Metro” and immediately jumped to “apparition” as ripe for analysis. How did it catch my eye? For me, this was unexpected language, something I didn’t anticipate. Roy Peter Clark makes a similar case in Writing Tools: if I say a character smiled grimly, I’ve created an interesting tension. And where there’s friction, there’s often fire. (If you’re a fan of Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays,” you’ll see something similar happening. The speaker refers to “love’s austere and lonely offices,” creating an unexpected perspective that merits our attention.)

Want another? Consider these lines from Theodore Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz”: “You beat time on my head / with a palm caked hard by dirt.” In the context of the full poem, “beat” can mean more than one thing: this is either a playful sense of meter, or it’s violent abuse. The poem hinges on that multiple meaning – making it a great place for our analysis.

The bottom line? Teaching knowledge and analytical techniques are only part of the equation for improving student thinking. We can push a level further by helping our students spot when passages and words are particularly inviting their additional scrutiny and thought. We need to find tune our students’ reading radar.