29 Nov If you want a great class debate, provoke it.

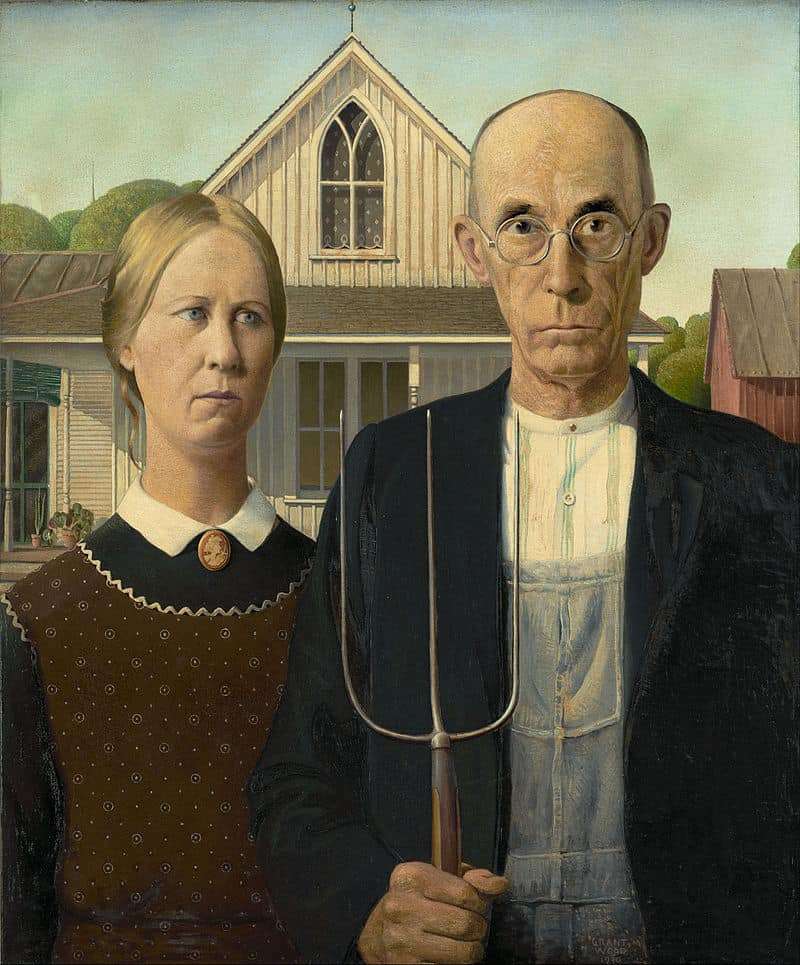

“There is satire in it, but only as there is satire in any realistic statement.”

Grant Wood, speaking about "American Gothic"

A short while back, I posted about the power of reframing argumentation in your classroom – moving from “argument is war” to something closer to “argument is truth seeking.” Perhaps that felt a bit utopian, but if you can build a classroom culture where disagreement isn’t done for sport, you open up lots of opportunities to supercharge engagement.

How? To answer, let’s take a cue from Grant Wood. Most likely, you’re familiar with his iconic American Gothic (above). Painted in 1930, it’s one of the most parodied paintings ever and one of the few most folks can recognize on sight. But why is that? When the painting was first created, it didn’t make immediate waves – netting only a very small third-place prize in a competition. If a student challenge you and said – “so why do people care?” – what would you reply?

Don’t worry – I’m not going to talk about repeating lines or stoic expressions. This painting, many agree, rose to prominence because it seeded a great debate. Some saw it as championing a return to “traditional” Americana, others as a satire of rural conservatism. And Wood, for his part, played this well – remaining inscrutable on the topic. TL:DR – the painting got popular because it’s easy and fun to disagree about what it means.

As long as your class community respects differing viewpoints, debates are a fantastic way to help students sharpen their ideas and engage deeply in class, just like how Grant Wood’s painting has done for museumgoers. For this, there are a few techniques that come in particularly handy:

- Highlight the debate that exists – if students are split on a question, name it for the class. Nothing perks up ears quite like: “we have a real debate forming.” This is a great moment to poll the class so folks can see the disagreement. And if you’ve framed debates as truth-seeking endeavors, everyone wins: those who shift the class consensus will be satisfied their ideas won the day, those who change their minds have just practiced a hallmark of intellectualism, and those who feel there still remain multiple possible “solutions” are seeing the world with nuance. One of the best parts of ELA class is that we can normalize disagreement without disdain.

- If a debate doesn’t exist, provoke one – I taught a 10th grade class that used to chronically agree with each other. Our discussions were polite, but students would typically take the first few things said as gospel. This felt friendly, but it wasn’t good for my students: it encouraged them to be intellectually complacent, and it sent a message that there was largely one way to go about reading a text. To break the habit, we did a few things:

- First, we introduced a new discourse habit: “Who can play devil’s advocate?” I’d ask – or I’d simply play this role myself. After modeling this a few times, students began to try it themselves with great effect. The idea that disagreement could be a useful tool for collaboration defanged the notion of challenging one’s peers, allowing students to problematize class thinking in way that felt playful. Here’s an example of students doing that in Danny Murray’s 11th grade English class. (pwd: uncommon1)

- Second, we switched to having small groups discuss topics before moving to large-class discussion. This allowed students to field test their ideas with a small crowd before going in front of the full room. The rehearsal time allowed students to refine positions and ultimately become more confident — and that further made the class space a safer place for disagreement.

- Finally, I shifted a few lessons to create debate – for example, by assigning students to argue specific cases. (When I did this, students had to argue a case for the first half of discourse, but were free to change sides for the second.) I know many of you out there can attest to the energy and joy that comes from putting characters on trial in class or having students argue points of view that may not be their own. We framed it as an intellectual challenge, and students rose to meet it.

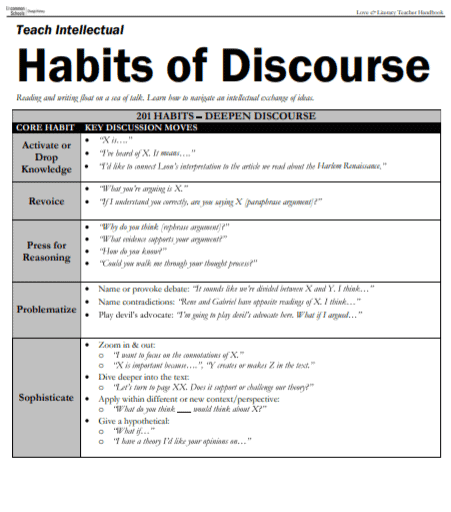

Debate isn’t the only way to deepen student thinking in discourse, but it’s a powerful option. It doesn’t need to happen by chance – and if you want to harness its power in class, you shouldn’t let it. Check out the second page of Uncommon’s “Habits of Discourse” guide, which offers some prompts to help students problematize groupthink or complicate conversations. Roll this out to students by modeling it yourself and then letting them give it a try.

Beth Verrilli, one of my mentors, used to say: “When all else fails, throw down a challenge.” There are few things that will get students’ blood pumping like the chance to defend or dissect an argument. And, if you’ve already framed argumentation as a respectful, communal endeavor, it won’t devolve into rudeness or blind competition.

You may have heard the famous line from William Butler Yeats: “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” Perhaps we can add some wisdom from Grant Wood – if you want to light a fire, sometimes you need a bit of friction.

***

PS The resources above come from Love and Literacy, my book with Paul Bambrick-Santoyo. Thanks to all of you have supported us. If you’ve given any of this a try in your room, drop me a line and let me know how it’s going!