11 Sep Literary Analysis: It’s Like Camerawork (part 1)

“I well remember that, availing himself of the synonyms to the Homer of Didymus, he made us attempt to show, with regard to each, why it would not have answered the same purpose; and wherein consisted the peculiar fitness of the word in the original text.” – Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria

One of the most common concerns I hear from teachers is that students are paraphrasing evidence when we want them to analyze it. But if we want students to dig deep into literature, often the root cause of the problem is that we haven’t clearly enough defined what it is that means. I want to explore this a bit.

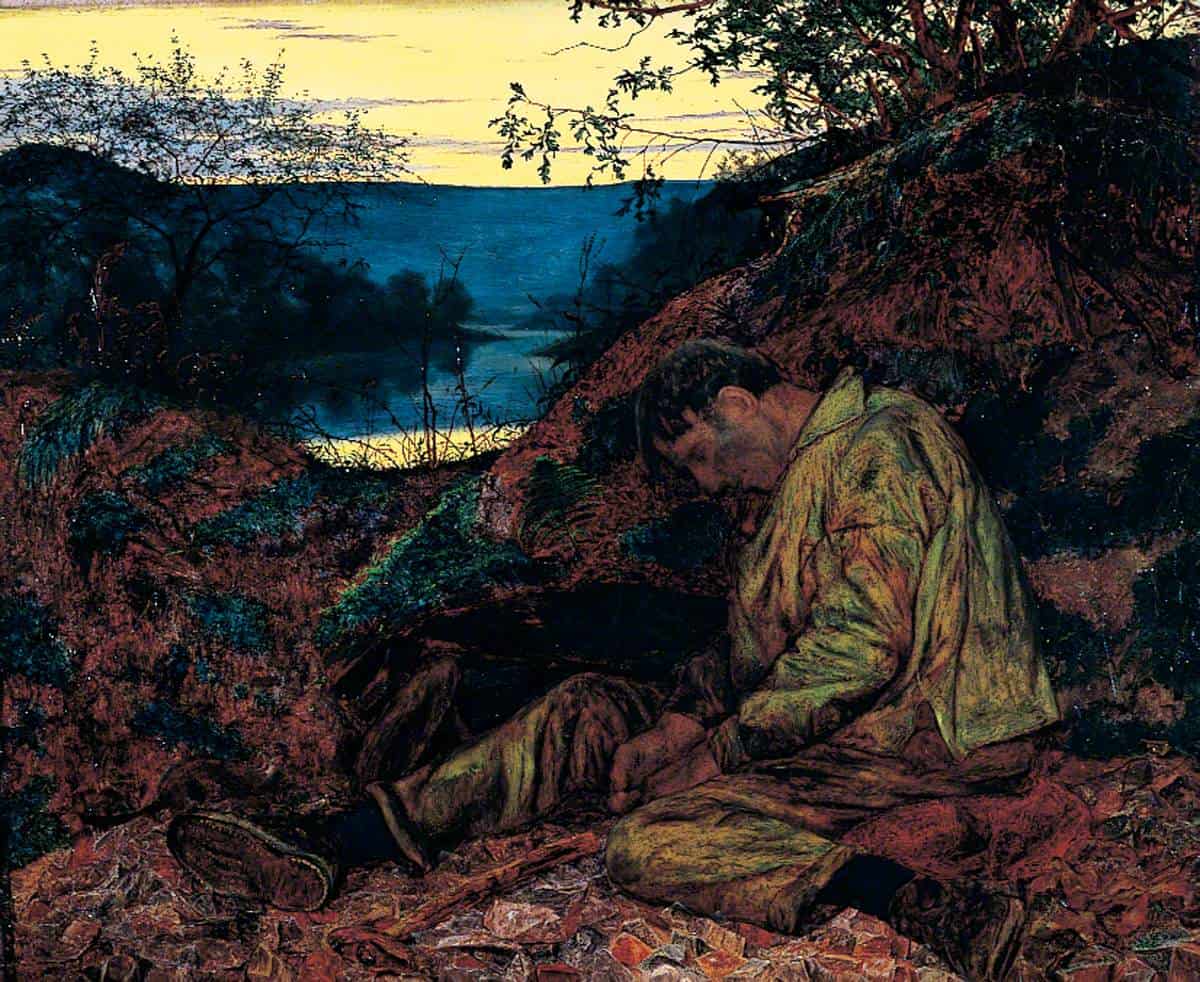

Sometimes the fastest way to think about literary analysis is to take a detour to art. So let’s spend a moment with Henry Wallis’s 1857 painting, The Stonebreaker. [It’s the painting that leads off this post.]

On first glance, the painting seems a bit peaceful – a worker resting after a day of toil, with

the sun dropping in the background. The lines are crisp, and they remind me a little bit of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations.

We could walk by this painting in the museum, admire its beauty and skill, and move on.

Consider, for example, the bottom left corner of the painting. (I’ll increase the brightness here, since we can’t get close.) The worker hasn’t laid his hammer down carefully – it’s just lying on the ground. And what’s that on his foot? An animal, a stoat, has simply crawled on top of it, but the man hasn’t woken up. Is he OK? This makes me want to revisit that beautiful sunset – perhaps it’s a metaphor for death, “as after sunset fadeth in the west.”

As I’ve previously written, a little additional background knowledge might go a long way. Stoats are generally timid — not the kind of animal that wants to crawl on a person and cuddle. And inscribed on the frame of this paining a paraphrase from Tennyson’s A Dirge: “Now is thy long day’s work done.” This increasingly feels like it’s a painting of a dead man – someone who has been literally worked to death. In fact, many critics view this painting as a protest against British working conditions.

So what did we do to begin an analysis? First, our background knowledge made a big difference. Knowing about the time period, or the painting’s frame, or even that sunsets sometimes refer to declining life all raised questions.

Beyond that, there were two key moves that Paul Bambrick-Santoyo and I have observed in classrooms and student work of powerhouse teachers:

Zoom in: Get closer to the level of the text. (Or look carefully at the painting, in this case.) What words or images did the author use? What do you associate with the language? Why this word and not another?

Zoom out: What are the implications of this choice? (AKA “So what?”) How does this choice contribute to the text?

For me, this is a bit more precise than the instructions we often give students (what/how/why or say/mean/matter), because it directs them to scrutinize the diction a bit further than they might otherwise. It also broadens our thinking from purely “author’s purpose” to the implications authorial choices have on our experience of a text. So analysis becomes less about deciphering unknowable experts and more co-creating meaning.

Take a line from Ezra Pound’s “In A Station of the Metro,” one of my favorite teaching texts (because it’s so compact, and because it was my least favorite poem as a student.) Here’s the whole thing:

The apparition of these faces in a crowd;

petals on a wet, black bough.

Let’s zoom in on “apparition.” Pound could have said image or likeness or appearance. But he chose “apparition,” something that feels fleeting and ghostly. To zoom out, I think about the effect this has on the text – to me, it suggests there’s something impermanent about the people he sees, a suggestion that the people here are transitory.

I could do the same steps on the next line, where Pound compares people to storm-tossed petals. There’s a randomness, even a violence suggested here. This poem definitely has more to say then “I saw a bunch of people at the train station yesterday,” and we can begin to investigate what that is by this process of zooming in and zooming out.

The bottom line? Great analysis is like great camerawork: zoom in, zoom out, repeat. In addition to building knowledge, we can use this language in class to help students build these habits of mind. Phrases like:

- “What words might you zoom in on here?” or

- “Let’s zoom out on what you’ve found” or

- “In your analysis, make sure you take the time to zoom in on any interesting diction you can find”

Great analysis is like great camerawork: zoom in, zoom out, repeat.

All help students build an analytical grammar that will serve them on the toughest texts – and maybe also on their next trip to the museum. But how is it that students know what they should zoom in on? That’s part 2. See you next time!

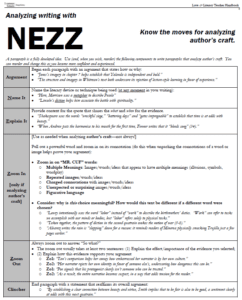

PS Want to see it in action? We’ve included videos, examples, and one-pagers in Love and Literacy, now available and a great way to start the year! If your school decides to run a book club, I’d be more than happy to visit via Zoom and answer questions! In the meantime, below is a 1-pager to help you get started: