02 May Making Reading Comprehension Visible

“We all seized the white perimeter as our own

and reached for a pen if only to show

we did not just laze in an armchair turning pages;

we pressed a thought into the wayside,

planted an impression along the verge.”

– Billy Collins, “Marginalia”

One of my Deep Nerd pastimes is reading about Medieval marginalia. Surrounding often austere or legal doctrine are often the most hilarious of images – whether it’s cats with rocket packs or a creature who looks suspiciously like Yoda or Grogu. For me, it’s a pleasant reminder that people have been silly, surprising and irreverent long before the likes of modern sensibilities came along.

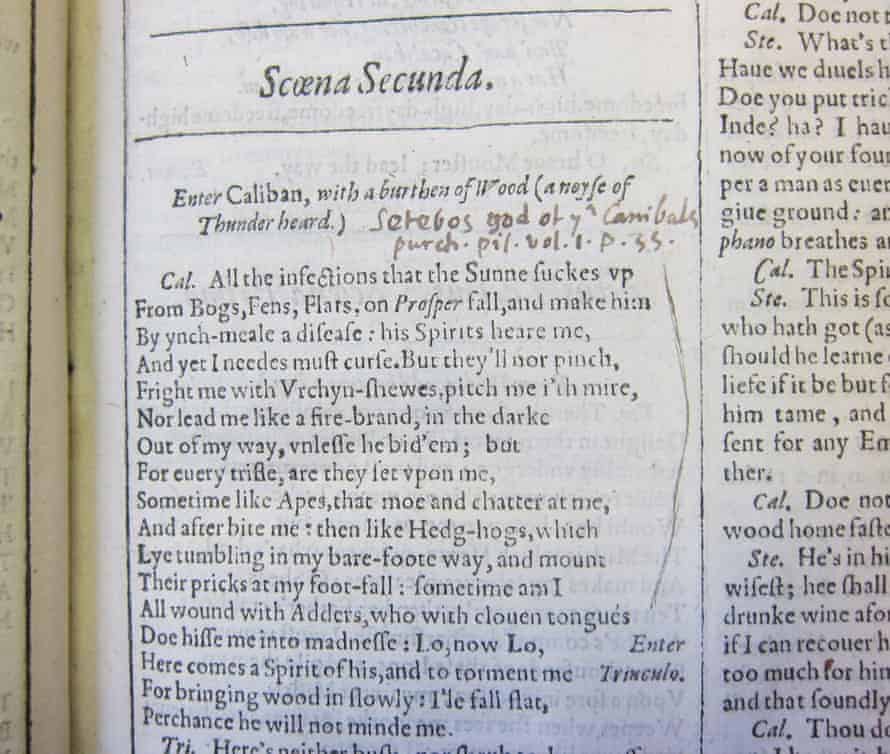

Annotations share something about the mind of the reader who made them. Consider the discovery that researchers made in 2019 – just the underlines in Milton’s copy of Shakespeare. Their complete giddiness about the find is powerfully endearing. As he began to realize what he’d uncovered, Cambridge fellow Jason Scott-Warren became “quite trembly … You’re gathering evidence with your heart in your mouth.” He noted that the underlines alone “give[s] you a sense of his sensitivity and alertness to Shakespeare.”

In my last post, I shared the guidance we provide to students to “read for claim,” a set of habits of mind that help students think through the structure and arguments in an informational text. (Here’s the one-pager I posted. It guides students, for example, to annotate claims as they find them in a text.)

But I was only able to tell part of the story last time: there’s another huge benefit to sharing this sort of guidance with students. It makes student thinking visible, line by line.

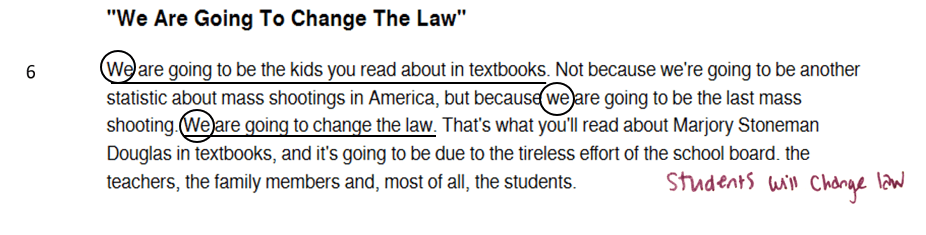

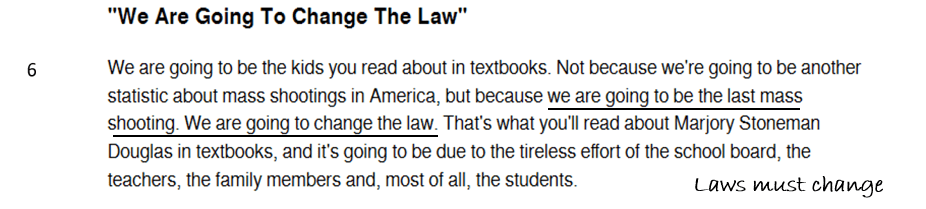

Consider this example from my forthcoming book with Paul Bambrick-Santoyo. I observed it a few years ago visiting the classroom of Mallory Grossman, then a star teacher, now a star instructional leader at one of our Newark schools. Mallory and her 6th graders were reading Emma Gonzalez’s “We Call BS” speech (which can be found at various Lexiles at Newsela.com).

Notice the difference between Mallory’s markup and the trend she saw from students.

Here’s Mallory’s exemplar annotation:

And here’s what most students had written.

Mallory has already introduced the notion of “Reading for Claim,” so she knows students are aiming to spot Gonzalez’s arguments. If they’re successful, they should have something in the ballpark of what she’s written.

On this day, however, they don’t. They’ve missed that Gonzalez was arguing it was specifically students who should be the changemakers. Mallory was able to address this right in the moment, directing students to reread and reannotate this section of the text, and share with a peer.

And it worked! Within minutes, students were back on course and had a much stronger experience with the text than they would have otherwise.

In his classic The Skillful Teacher, John Saphier and his colleagues remark on the power of making students’ thinking visible. It’s only then that we can truly support them where they need us.

So if we lay out some universal expectations for annotation, not only does it help students build habits of mind, but it allows us to look at their texts – both during and after class – to see what ideas they may be missing.

The bottom line?

When we read on our own, our annotation systems are often personal (or sometimes non-existent!).

But in class, setting shared expectations for annotation is a powerful way to help students practice strong habits of mind and make their thinking visible. Like Mallory, if we can determine precisely where students are struggling, we know exactly where to meet them.

Annotations help students understand texts. But they help educators understand students.